Sometimes when a study comes out that I’m very interested in blogging about, I don’t get around to it right away. In the blogging biz, this sort of delay is often considered a bad thing, because blogging tends to be very immediate, about being the firstest with the mostest, and the moment to strike and be heard about major studies is brief. Of course, there’s also real life as well. That this particular study came out in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) didn’t help. So, here it is, a week and a half later, and I’m finally getting around to it. There is, however, an advantage to this delay in my usual due diligence.

The cranks have had a chance to discover the study.

I must admit, it took the cranks longer than I thought it would, but discover it they did. So I think I’ll start by introducing the study the way the medical crankosphere. And who is more of a crank than Mike Adams, creator of the über-quack site NaturalNews.com, who declares, Mammograms a medical hoax, over one million American women maimed by unnecessary ‘treatment’ for cancer they never had:

Mammography is a cruel medical hoax. As I have described here on Natural News many times, the primary purpose of mammography is not to “save” women from cancer, but to recruit women into false positives that scare them into expensive, toxic treatments like chemotherapy, radiation and surgery.

The “dirty little secret” of the cancer industry is that the very same oncologists who scare women into falsely believing they have breast cancer are also the ones pocketing huge profits from selling those women chemotherapy drugs. The conflicts of interest and abandonment of ethics across the cancer industry is breathtaking.

Now, a new scientific study has confirmed exactly what I’ve been warning readers about for years: most women “diagnosed” with breast cancer via mammography never had a cancer problem to begin with!

Meanwhile, Sayer Ji, whom we’ve met before at GreenMedInfo.com, a website that wildly twists new scientific studies to make it sound as though they support and justify quackery, exults, 30 Years of Breast Screening: 1.3 Million Wrongly Treated:

The breast cancer industry’s holy grail (that mammography is the primary weapon in the war against breast cancer) has been disproved. In fact, mammography appears to have CREATED 1.3 million cases of breast cancer in the U.S. population that were not there.

A disturbing new study published in the New England Journal of Medicine is bringing mainstream attention to the possibility that mammography has caused far more harm than good in the millions of women who have employed it over the past 30 years as their primary strategy in the fight against breast cancer.[i]

Titled “Effect of Three Decades of Screening Mammography on Breast-Cancer Incidence,” researchers estimated that among women younger than 40 years of age, breast cancer was overdiagnosed, i.e. “tumors were detected on screening that would never have led to clinical symptoms,” in 1.3 million U.S. women over the past 30 years. In 2008, alone, “breast cancer was overdiagnosed in more than 70,000 women; this accounted for 31% of all breast cancers diagnosed.”

To which Adams can’t help but to go beyond this study and repeat his usual baseless broadsides against science-based cancer therapy:

Pure quackery! You could do much better invoking voodoo or even just wishing to be cured. Because everything about the cancer experience in modern medicine — the diagnosis, the “treatment,” the medical authority — is utterly and maliciously fabricated for the purpose of generating cancer industry profits.

It’s rather ironic that Adams would refer to invoking voodoo or “just wishing to be cured,” given that that’s what he and much of the alternative cancer industry actually does recommend, whether it be the German New Medicine or Biologie Totale, which basically posits that cancer is reaction to a “psychic trauma” that the patient has to work through, various “energy healing” modalities that are nothing more than faith healing, or the more “mainstream” belief that a positive attitude can prolong the lives of cancer patients, an idea whose basis in science is minimal. I’ve even heard from quacks about the “wisdom” of cancer cells, as though cancer were a survival mechanism that you can consciously control.

It ain’t.

After reading this study, my first thought was: Here we go again. My second thought was: Wow. The result that one in three mammographically detected breast cancers might be overdiagnosed is eerily consistent with a study published three years ago that looked at mammography screening programs from locations as varied as the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Sweden, and Norway, which I discussed at the time it was released. The consistency could mean either convergence on a “true” estimate of overdiagnosis, or it might mean that both studies shared a bias, incorrect assumption, or methodological flaw. If they do, I couldn’t find it, but it’s still an intriguing similarity. In any case, let’s dig in. The article is by Archie Bleyer and H. Gilbert Welch (the latter of whom has featured prominently in this blog several times before) and is entitled Effect of Three Decades of Screening Mammography on Breast-Cancer Incidence.

Overdiagnosis and overtreatment in diseases we screen for

Before I go on I feel obligated to point out, as I always do when this subject comes up, that what I am referring to here are breast cancers detected by screening mammography in asymptomatic women. I cannot emphasize this enough. This study (and most of the studies I blogged about above) do not apply to women who have detected a lump, suspicious skin change, or any other symptoms of breast cancer. For such women, as far as we’ve been able to ascertain, the likelihood of overdiagnosis is vanishingly small. These cancers will almost certainly progress. Therefore, this study and my post do not apply to these cancers. If you feel a lump in your breast, get it checked out. If it is cancer, it will not fail to progress, nor will it go away. Again, I cannot emphasize this enough.

Regular readers are, I hope, familiar with the concept of overdiagnosis; so I’ll hope those who’ve read our discussions will bear with me a moment as I review the concept for those who might not be familiar with the concept. In doing so, I’ll steal shamelessly from my previous writings, after pointing out that it four and a half years ago when I first pointed out that the relationship between early detection of cancer—any cancer—and improved survival is more complicated than most people, even most doctors (including oncologists), think.

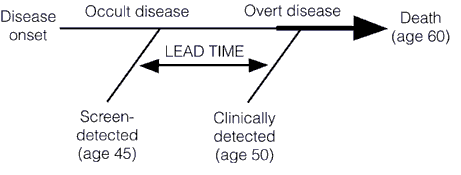

Screening for a disease involves subjecting an asymptomatic population, the vast majority of whom don’t have the disease, to a diagnostic test in order to find the disease before it causes symptoms. This is very different from most diagnostic tests used in medicine, the vast majority of which are ordered for specific indications. Any test to be contemplated for screening thus has to meet a very stringent set of requirements. First, it must be safe. Remember, we’re subjecting asymptomatic patients to a test, and invasive tests are rarely going to be worthwhile, except under uncommon circumstances (colonoscopy screening for colon cancer comes to mind). Second, the disease being screened for must be a disease that is curable or manageable. It makes little sense to screen for a disease like amyotropic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig’s disease) because there is very little that will slow its progression. The one drug that we do have, Riluzole, only slows the progression of ALS slightly. Thus, diagnosing ALS a few months or a few years before symptoms appear won’t change the ultimate outcome. A very important corollary to this principle is that acting to treat or manage a disease early, before symptoms appear, should result in a better outcome, and the authors of this study point this out. I’ve discussed the phenomenon of lead time bias in depth before; it’s a phenomenon in which earlier diagnosis only makes it seem that survival is longer because a disease was caught earlier when in reality treatment had no effect on it. The condition progresses at the same rate as it would without treatment. Lead time bias is such an important concept that I’m going to republish the diagram I last used to explain it, because in this case a picture is worth a thousand words:

Then there’s this graph, from this paper, that demonstrates how screening preferentially detects less aggressive cancers (more details in my post here):

Another requirement for a screening test is that the disease being screened for must be relatively common. Screening for rare diseases is simply not practical from an economic standpoint. Economics aside, it’s bad medicine, too, because vast majority of “positive” test results will be false positives. Another way of saying this is that the specificity of the test must be such that, whatever the prevalence of the disease in the population, it does not produce too many false positives. In other words, for less common diseases the specificity and positive predictive value must be very high (i.e., a “positive” test result must have a very high probability of representing a true positive in which the patient actually does have the disease being tested for and the false negative rate can’t be too high; either that, or screeners must be prepared to do a lot of confirmatory testing for a large number of false positives). For more common diseases, a lower positive predictive value is tolerable. The test must also be sufficiently sensitive that it doesn’t produce too many false negatives. Remember, one potential drawback of a screening program is a false sense of security in patients who have been screened, a drawback that will be increased if a test misses too many patients with disease. Finally, a screening test must also be relatively inexpensive.

So what is overdiagnosis? Stated simply, overdiagnosis is a term used to describe disease detected in asymptomatic individuals that would never go on to threaten the life or health of those individuals. Many people subscribe to a simplistic view of cancer in which after the initial transforming event occurs to create a cancer cell the cancer will inevitably progress over time until, if left untreated, it will kill the individual. In such a view, detecting cancer earlier is an unalloyed good because it is assumed that, if left untreated, such tiny cancers will inevitably progress. However, as I first started to point out a few years ago, this is not necessarily true. people have a lot of cancer in them that never causes a problem. For instance, it’s well known that autopsy series reported on who died at age 80 or older have consistently shown that the majority of men over 80 (60-80%) have detectable foci of prostate cancer. Yet, obviously prostate cancer didn’t kill the men in these autopsy series, and they lived long enough to die either of old age or a cause other than prostate cancer. In other words, they died with early stage cancer but not of that cancer. Similarly, thyroid cancer is pretty uncommon (although not rare) among cancers, with a prevalence of around 0.1% for clinically apparent cancer in adults between ages 50 and 70. Finnish investigators performed an autopsy study in which they sliced the thyroids at 2.5 mm intervals and found at least one papillary thyroid cancer in 36% of Finnish adults. Doing some calculations, they estimated that, if they were to decrease the width of the “slices,” at a certain point they could “find” papillary cancer in nearly 100% of people between 50-70.

The list of conditions and diseases for which screening has increased apparent incidence goes on and on far beyond cancer.

One might ask what the problem is with overdiagnosis; i.e., what’s the harm? The harm arises from the consequence of overdiagnosis, which is overtreatment. If the screen-detected condition, be it tumor or other medical condition, would never progress to harm the patient even if untreated, then “treating” that condition can only cause harm, not benefit. That’s not even counting the risks from additional followup studies that are frequently required when a screening test finds an abnormality. In the case of breast cancer, the subject of the current study, those additional tests might mean more images (and the extra radiation they involve), invasive needle biopsies, and even surgical biopsies. In the case of screening for lung cancer, biopsies are more risky than for breast cancer, given the large blood vessels in the lung and the ease with which the a pneumothorax can occur. All mass screening programs involve a tradeoff, a balancing of risks and potential benefits, and it’s not even always clear how great the benefits might be. For instance, lead time bias can lead to an overestimation of benefits of treatment and a huge apparent increase in survival even if treatments don’t have an effect on the disease. That’s why mortality rates are the appropriate metric, not five-year survival rates, when evaluating a disease for which lead time bias is a consideration. It’s also why, when we do use survival rates in cancer, in order for them to be comparable they have to be stage-adjusted.

On to the study

In order to understand Welch’s study, it is important to realize that there is a huge assumption underlying its methods. That assumption, although reasonable, is not unassailable (more on that later). Specifically, as Welch states in the very first paragraph:

There are two prerequisites for screening to reduce the rate of death from cancer.1,2 First, screening must advance the time of diagnosis of cancers that are destined to cause death. Second, early treatment of these cancers must confer some advantage over treatment at clinical presentation. Screening programs that meet the first prerequisite will have a predictable effect on the stage-specific incidence of cancer. As the time of diagnosis is advanced, more cancers will be detected at an early stage and the incidence of early-stage cancer will increase. If the time of diagnosis of cancers that will progress to a late stage is advanced, then fewer cancers will be present at a late stage and the incidence of late-stage cancer will decrease.3

In other words, a screening test that does not overdiagnose will find cancers earlier. These cancers will be successfully (or at least more successfully) treated, and thus pulled out of the pool of early stage cancers that are progressing to late stage cancers. This removal of early stage cancers from the total pool of cancer diagnoses should thus shift the stage distribution of breast cancer to earlier stages and result in an absolute decrease in the number of late stage cancers being diagnosed. In other words, as the number of cancers being detected early goes up, the number of cancers being detected at advanced stages, particularly at stage IV (which can be treated but not cured), should go down. Thus, the overall hypothesis is that, if mammography is effective, there should be an increase in the incidence of early stage cancer diagnosed and a corresponding decrease in the incidence of late stage cancer. If the diagnosis of early stage cancer increased faster than the diagnosis of late stage cancer decreased that likely represents overdiagnosis.

To test this hypothesis and try to estimate the amount of overdiagnosis going on, Welch used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database to examine stage–specific incidence of breast cancer over time. This database covers approximately 10% of the U.S. population. Using such a database was complicated by two issues. First, the authors had to choose a baseline, more specifically, a time period that they set as their baseline breast cancer incidence for cancers detected without mammography. For various reasons, including an underestimate in the earliest years of the SEER database in the early 1970s and because of a brief spike in breast cancer diagnoses in the wake of Betty Ford’s diagnosis, the authors chose 1976 to 1978 as this baseline. Second, there was a period from the late 1980s to early 2000s when hormone replacement therapy with mixed estrogen-progesterone combinations was popular and is widely believed to have increased the incidence of breast cancer. This time period, according to the authors, ended in 2006. To correct for this in current estimates of breast cancer incidence from 2006 to 2008, they truncated the observed incidence from 1990 to 2005 to remove “excess” cases from previous years. This part of the approach actually puzzled me a bit, because although it would result in a lower apparent incidence of breast cancer it’s not clear how it would do what the authors stated and “provide estimates that were clearly biased in favor of screening mammography — ones that would minimize the surplus diagnoses of early-stage cancer and maximize the deficit of diagnoses of late-stage cancer”; i.e., provide a “best case scenario” for screening mammography.

Another area where I quibble a bit with Welch is his assumption that the change in the incidence rate of breast cancer among women under 40 (who do not undergo screening in this country) is a valid estimate of the true incidence of breast cancer. Breast cancer in women under the age of 40 is arguably biologically different than the more “typical” breast cancer. At the very least, it tends to be more aggressive. I realize that in the SEER database there is no better surrogate for the incidence of breast cancer in an unscreened population, but the question of the biological relevance of this “control” group was pretty much glossed over in this paper.

The first “money” figure is Figure 1, which shows the incidence of early and late stage cancer over time:

There are two things to note here. First, as I’ve discussed before on multiple occasions, the apparent incidence of early stage breast cancer skyrocketed after the introduction of mass mammography screening programs in the late 1970s and early 1980s and has only leveled off in the last six or seven years. Second, the incidence of cancers diagnosed at late stage did decrease, but not by a lot. The authors state:

The large increase in cases of early-stage cancer (from 112 to 234 cancers per 100,000 women — an absolute increase of 122 cancers per 100,000) reflects both detection of more cases of localized disease and the advent of the detection of DCIS (which was virtually not detected before mammography was available). The smaller decrease in cases of late-stage cancer (from 102 to 94 cases per 100,000 women — an absolute decrease of 8 cases per 100,000 women) largely reflects detection of fewer cases of regional disease. If a constant underlying disease burden is assumed, only 8 of the 122 additional early diagnoses were destined to progress to advanced disease, implying a detection of 114 excess cases per 100,000 women. Table 1 also shows the estimated number of women affected by these changes (after removal of the transient excess cases associated with hormone-replacement therapy). These estimates are shown in terms of both the surplus in diagnoses of early-stage breast cancers and the reduction in diagnoses of late-stage breast cancers — again, under the assumption of a constant underlying disease burden.

I’ve discussed how mammography has increased the apparent incidence of DCIS before. The observation that increased screening for virtually any condition can and does reliable result in the detection of preclinical disease and an increase in incidence is perhaps nowhere better shown that for the case of mammography and DCIS.

The second “money figure” (in this case, “money table”) from the paper is Table 2, which looks at the excess estimation of breast cancers by screening mammography based on four assumptions a base case (constant “underlying” incidence of breast cancer); best guess (breast cancer incidence rising at 0.25% per year, as estimated from the rate of increase of breast cancer incidence in women under 40); an extreme assumption (breast cancer incidence increasing 0.5% per year, twice that of the “best guess”) and a “very extreme assumption” (0.5% per year increase in breast cancer incidence plus using the highest estimate of baseline incidence of late stage disease). Here’s the table:

The authors point out that, regardless of the method they used to calculate it, their estimate of the number of women overdiagnosed with breast cancer over the the last 30 years was at least 1 million, and the proportion of cancers that were overdiagnosed were 31%, 26%, and 22% in the best guess, extreme, and very extreme estimates, respectively.

Although Welch’s estimate is consistent with a growing literature that is consistent with a rate of overdiagnosis for screen-detected breast cancers of over 20%, there are still problems with it. Most of these problems derive from using SEER data. For one thing, SEER is often slow to incorporate new clinical and scientific findings. For example, a few years ago I wanted estimates of the number of patients in our SEER catchment area who are HER2-positive. I couldn’t get it, because at the time SEER hadn’t yet incorporated HER2 status into its database, even though it had been used as a prognostic marker for several years before. SEER does now incorporate HER2, but the point is simply that it’s often behind the times because it’s a big database and decisions regarding how to change in response to evidence and new clinical findings often come slowly.

Another issue is how stage definitions change over the years. However, perhaps one thing that I might have expected someone like Welch to consider but that he apparently did not (at least not if his discussion is any indication) is the issue of stage migration. Welch defines his stages thusly:

The four stages in this system are the following: in situ disease; localized disease, defined as invasive cancer that is confined to the organ of disease origin; regional disease, defined as disease that extends outside of and adjacent to or contiguous with the organ of disease origin (in breast cancer, most regional disease indicates nodal involvement, not direct extension9); and distant disease, defined as metastasis to organs that are not adjacent to the organ of disease origin. We restricted in situ cancers to ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), specifically excluding lobular carcinoma in situ, as done in other studies.10 We defined early-stage cancer as DCIS or localized disease, and late-stage cancer as regional or distant disease.

Fair enough, as far as it goes. However, when one looks at breast cancer over 30 years, one can’t help but note that how we detect node-positive disease (i.e., regional disease) has changed. In fact, the new standard of care, known as sentinel lymph node biopsy, can detect lymph nodes with much smaller tumor burdens, particularly when immunohistochemical stains are used, which could mean that over the last decade or so we could be seeing stage migration, largely as a result of detecting smaller metastases. Stage migration is a phenomenon that occurs when more sophisticated imaging studies or more aggressive surgery leads to the detection of tumor spread that wouldn’t have been noted in an identical patient using previously used tests. What in essence happens is that technology results in a migration of patients from one stage to another. This is not an insignificant consideration. One study suggested that the stage migration rate was as high as one in four; i.e., 40% of patients having “positive” axillary lymph nodes with SLN biopsy compared to 30% having positive nodes using axillary dissection. Another study reported similar results. How this would affect Welch’s analysis is hard to tell, and correcting for it is probably not possible using the SEER database, particularly given that the extent of “up-staging” is not fully known yet. Be that as it may, an increase in the apparent incidence of patients with positive lymph nodes would increase the apparent incidence of advanced disease and decrease any decline in the incidence of advanced disease. How large this effect is, I don’t know, but it would suggest that the rate of overdiagnosis is lower than what Welch estimates. How much lower, or whether stage migration is even a significant factor, I don’t know, but I wish that Welch had at least mentioned it.

The bottom line

This latest study by Bleyer and Welch is not, as I’m sure some proponents of “alternative” therapies and “alternative” means of diagnosing breast cancer, such as thermography, will try to argue, evidence that mammography doesn’t work or that it doesn’t save lives. It does. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that. However, those trials are old, and it’s not infrequent that “real world” applications of medical tests and treatments will be less effective than demonstrated in RCTs. There is also the “decline effect” to contend with, and I sometimes wonder whether the re-evaluation of mammography that is going on right now is simply one more example of a test not being as good as RCTs originally suggested. On the other hand, there are studies (for instance, this one) that strongly suggest mammography’s value in saving lives, even in younger women (aged 40-49), for whom there is the most controversy regarding mammographic screening.

Be that as it may, the Bleyer and Welch study is simply more evidence that the balance of risks and harms from mammography is far more complex than perhaps we have appreciated before. It’s very hard for people, even physicians, to accept that not all cancers need to be treated, and the simplicity of messaging needed to promote a public health initiative like mammography can sometimes lead advocacy groups astray from a strictly scientific standpoint. One has only to look at the reactions of some doctors to see this. For instance:

The study was roundly criticized by radiologists who specialize in breast imaging, who questioned its methodology and the suggestion that some cancer-like growths should be ignored.

“It’s kind of unbelievable that they’re telling us we’re finding too many early-stage cancers,” said Dr. Stamatia Destounis, a breast imager in Rochester, N.Y. “Isn’t that the point?”

And:

“This is simply malicious nonsense,” said Dr. Daniel Kopans, a senior breast imager at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. “It is time to stop blaming mammography screening for over-diagnosis and over-treatment in an effort to deny women access to screening.”

Dr. Kopan, I’m afraid, is completely wrong. This study is not “malicious nonsense.” It has weaknesses and might well overestimate the rate of overdiagnosis, but overdiagnosis is a real phenomenon. Only someone utterly ignorant of basic cancer biology or (as I suspect) protecting his turf would say something so nonsensical (word choice intentional). We’ve seen him say these sorts of things before, most prominently in response to the USPSTF guidelines proposed three years ago when he made dire warnings that large number of women will die because of them and said of the members of the task force, “I hate to say it, it’s an ego thing. These people are willing to let women die based on the fact that they don’t think there’s a benefit.”

As I said, it’s hard for many physicians to accept that not all cancer necessarily needs treatment. Certainly this is likely to be true for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), which consists of cancerous cells that have not yet invaded through the basement membrane of the ducts. Unfortunately, this is the predominant form of breast cancer that is detected by mammography. Indeed, the authors even point out that their method didn’t allow them to disentangle the incidence of DCIS from that of invasive breast cancer, thanks to the way that the SEER database is set up. The problem, of course, is that we don’t know how to predict which cancers will progress and which cancers will not.

Finally, for all the confusion this study causes, there is one spot of good news, and that’s the observation that much of the decline in breast cancer mortality over the last 20 years—yes, contrary to what you might have heard, breast cancer mortality has actually been steadily decreasing—is likely due to improvements in treatment. The authors point this out:

Whereas the decrease in the rate of death from breast cancer was 28% among women 40 years of age or older, the concurrent rate decrease was 42% among women younger than 40 years of age.6 In other words, there was a larger relative reduction in mortality among women who were not exposed to screening mammography than among those who were exposed. We are left to conclude, as others have,17,18 that the good news in breast cancer — decreasing mortality — must largely be the result of improved treatment, not screening. Ironically, improvements in treatment tend to deteriorate the benefit of screening. As treatment of clinically detected disease (detected by means other than screening) improves, the benefit of screening diminishes. For example, since pneumonia can be treated successfully, no one would suggest that we screen for pneumonia.

Ironically, it might be that one of the reasons that the mammography wars are heating up again, with concerns of overdiagnosis and overtreatment beginning to call the benefits of mammography into question might be that mammography is a victim of the success of breast cancer treatment. The multidisciplinary combination of surgery, chemotherapy and targeted therapies, and radiation oncology has made breast cancer treatment, even for relatively advanced cases, far more effective than it was 30 years ago. It might be that treatments for breast cancer have improved so much over the last couple of decades that the role of mammography will inevitably decline. Maybe.

There is, however, a lot more that needs to be done before we can conclude that; right now reports of the death of mammography are very premature. To me, what is most important in breast cancer screening right now is to develop reliable predictive tests that tell us which mammographically detected breast cancers an be safely observed and which ones are likely to threaten women’s lives. We are currently at a point where imaging technology has outpaced our understanding of breast cancer biology, or, as Dr. Welch put it, “Our ability to detect things is far ahead of our wisdom of knowing what they really mean.” Until our understanding of biology catches up, the dilemma of overdiagnosis will continue to complicate decisions based on breast cancer screening.

Of course, cranks and quacks like Mike Adams and Sayer Ji look for any evidence of flaws or shortcomings in conventional medicine and then blow them up to argue that “medicine doesn’t work.” The intended implication is that any shortcoming in science-based medicine means that their woo must be a credible alternative.

It ain’t.

37 replies on “Crank spin versus science on mammography”

I will agree that we have problems with certain entities, such as low grade intraductal carcinoma, some of which may need to be reclassified as atypical hyperplasia, but I have some problems with the rest of this study.

First, looking at the supplemental information, it’s clear that the study was based entirely upon ICD-9 codes. This means that the study relies entirely on the accuracy of coding. There seems to have been no attempt made to check on coding accuracy or to review slides to make sure that diagnoses were correct (and I do recognize the difficulty and expense of this, but it is necessary to at least do some spot checking; at least for more recent cases coding accuracy could be verified by computer searches).

Second, because the study was based upon ICD-9 codes, no attempt was made to remove cases that are known to be indolent, such as tubular and mutinous carcinomas, from the sample.

I agree that the under 40 group should be removed from the study. This population is likely to be enriched with BRCA mutation carriers who may be biologically distinct from the general population.

In short, I think that this study should be repeated with these adjustments (necessarily on a smaller sample). Until then, I do not think there is enough presented in this paper to recommend changing the screening protocols.

I now have a topic that could take a couple weeks to wade through – performance enhancing drugs. Found a link, googled the first thing that piqued my curiousity: Anti aromatase

It’s a what? Oversimplified explanation is that it suppresses estrogen production.

So why are athletes taking it? To counter the breast building effects of some anabolic steroids.

I am not sure what to think. Should I blame Big Pharma? Big Sports? Society?

I get to Wonder at the stupidity of Mike Adam’s statement that cancers are caused by psychic trauma. Not only I have to look at myself (currently free of cancer) but also, there isn’t a high incidence of cancers in soldiers afflicted with PTSD.

Alain

Dr. Finfer – The under-40 women were used only to provide an estimate of what increase in breast cancer would be expected without screening. The authors knew that readers sharing your opinions would say “Well, maybe the rate of breast cancer would have skyrocketed over the past thirty years without screening, thus explaining why a amiserably small decrease in advanced cancers is really a big win.” If our environment has in some way become more cancer-inducing, women with BRCA genes should be more susceptible than others, so if anything they would show a higher rate of increase. The exception is that they aren’t exposed to HRT, but that was corrected for.

BTW, Orac, the correction for HRT-induced cancer seems very reasonable to me. In deciding when and how often to get screened, I want to know the absolute chances that I will receive a useful early diagnosis, a non-useful early diagnosis, or an overdiagnosis, and I want to know how many overdiagnoses there are for every useful diagnosis. That depends upon the numbers of both harmless and “real” cancers. If the number of real cancers was greater in the past because of HRT, then a fixed number of overdiagnoses would have represented a smaller percentage of total diagnoses. In the future, very few of us are going to let ourselves be put on that stuff for life, so those numbers no longer apply.

@ Alain:

Right, that’s another harmful- and nonsensical- belief rife in woo-ville. As well as another way to BLAME victims.

In their ( ridiculous ) book, a person gets cancer because they either ate, drank, breathed, thought wrongly or reacted to a trauma in the wrong way- i.e. emotionally. Of course, they THEMSELVES would have had no such problem, being miraculously close to perfection as they assure us they are. Frequently.

So what are they REALLY saying? That there’s something inferior about the victim who is not invulnerable to environmental assaults UNLIKE themselves. The head idiot @ PRN talks about those who fail when taking the cure ( i.e. his own vegan, mostly raw, gluten free, GMO-free, organic, pure food and mega-supplement regime)- they OBVIOUSLY did not “de-stress”( his word, not mine) and become spiritual enough- they carried around anger, egotism and BLAME**. They were not peaceful, humanitarian or enlightened – like he is. Truthfully, there is nothing wrong with the treatment thus there must be something wrong with the patient. ( Similarly, they blame death on chemotherapy not on cancer- which makes cancer out to be a weak force-it can’t hurt you, just like VPDs)

Not only is this a way to avoid responsibility for his own prescriptions BUT it is a way for him to deny the possibility that anyone- despite rank, station, diet, fitness level or wealth- CAN get sick and DIE. Remember that this is the same person who avows that you – by doing right, like he does- can live to 140. His parents, relatives and brother died before 60 because they didn’t live right and listen to him.

** I know. Ironic.

Off topic to breastcancer: Steven Salzberg has posted at Forbes: Congress holds an anti-vaccination hearing

http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevensalzberg/2012/12/03/congress-holds-an-anti-vaccination-hearing/

The comments are infested with the Dachelbot, Joe99, Twyla.. Dr. Salzberg neads some help.

I find fascinating how those quacks think.

Studies like that are a proof that science *works*. Not that science doesn’t work.

But for them, being proven wrong is The End. In science, being proved wrong just means you have to adjust your aim, so to speak.

@ Liz Ditz:

Lovely comments there.

AoA and TMR have been bubbling with vitriol since the meeting. I am truly pleased that this computer doesn’t allow me to watch videos – thus I am spared – partially.

@Orac

“It ain’t.”

Used to implicitly strengthen your attack on people based on … nothing? Come on, what do you intend to show with such irrelevant passive offensive short phrases? Given their existence though, please provide an evidence for your “It ain’t” statements. Otherwise, it’s total ignorance from your side.

I don’t remember ancients being able to provide a scientific evidence for the Earth being round; however, lack of evidence at that time did not imply lack of actuality. What is true and real is only softly correlated to scientific evidences. You don’t seem to understand that scientific evidence is mostly based on “sensing”, so if the technology underlying “sensing” is yet to be developed, scientific evidence cannot be provided. What is not science-based today may become science-based tomorrow and your ego-centered definitive black-and-white “Yes or No” statements are of no use.

Without even getting to Eratosthenes, I’d say the plain existence of the horizon counts as “a scientific evidence.”

“Thus, if eclipses are due to the interposition of the earth, the shape must be caused by its circumference, and the earth must be spherical.”

— Aristotle, “De Caelo”, Book II, Ch. 14.

“What is not science-based today may become science-based tomorrow and your ego-centered definitive black-and-white “Yes or No” statements are of no use.”

Jim — you have utterly missed the point of Orac’s post. in science, there are no definitive black-and-white “yes” or “no” statements, even though folks like Adams want us very much to believe that there should be.

And what Narad said. The ancients knew the Earth was round because there was actually quite a bit of evidence available to them. In addition to various ways of deducing it from the horizon (the most obvious of which is ships disappearing over it), there is also the one you see any time there is a lunar eclipse — you can see the edge of the Earth’s shadow.

A lot of people use things the ancients didn’t know as an argument of how things exist that you don’t know about, but it’s interesting how frequently they pick something the ancients actually *did* know. (For instance: Columbus never proved the Earth was round. Nobody wanted to fund him because he thought the Earth was much smaller than it really is and they all figured his crew would starve to death on the voyage. Which they would have, if the Americas hadn’t turned up. He was a very lucky idiot.)

Heh; I see Herr Docktor has posted at the same time as I about lunar eclipses. 😉

Liz Ditz: I popped a few words in, but I have to admit the rate that they are posting trash over there is a bit over-whelming.

Jim: There’s a surprising number of deductions of the spherical nature of the earth from quite early on. (I’ve no idea what you mean by “the ancients”.) You can also use the length of shadows cast at different places on the earth to deduce the curvature, for example.

I wonder why Mr Adams never pops his head over the parapet which is RI.

Worryingly though, while I agree with all our beloved plastic box said, I played (in my mind) devils advocate.

I could cherry pick and cut and paste sentences so well even Servilan would be impressed.

The over 40 population has been ageing, with more and more living into their 80’s. There is no mention in the abstract of adjustment for that. Is it covered in the full article? I’d expect this to increase the expected number advanced cancers. Admittedly the 0.5% p.a. increase case might cover it.

Diagnostic stage migration seems to be the biggest flaw here.

@ Denice,

speaking about harm, where does that come from, this phrase: what doesn’t kill you make you stronger?

I’m pretty sure this could be an adage popular in woo-ville.

Alain

@Alain:

Soldiers with PTSD clearly haven’t manifested their cancer yet! Don’t you know psychic trauma affects your aura for decades? Mark my words, the U.S. is going to have a massive spike in cancer cases in about 10 years time.

After all, if I get a vaccine today and a rash in a week’s time, it’s clearly a vaccine injury. Same thing with psychic trauma and cancer.

Err, that last comment was sarcastic in case anyone is wondering. I put an end-sarcasm tag in but it got eaten.

Mark my words, the U.S. is going to have a massive spike in cancer cases in about 10 years time

fair enough but I’ll defer to Orac for lead time bias of the different cancer we could be afflicted (if breast cancer is an indication, 10 years would be the equivalent of DCIS).

Alain

@ Alain:

It’s Nietzsche and a quote with which I heartily disagree most emphatically- and might even re-phrase as:

*Whatever doesn’t kill you might so cripple you and cause you such great misery that you might be better off dead*

Nietzsche has serious psychological problems ( of syphylitic origin, IIRC) and was used as an an example of deranged thought process by Jung, who looked at his writings in detail.

@ Peebs:

Adams is quite aware of Orac, having mentioned him a while back. Similarly, one of Null’s minions ( Richard Gale) spoke about Orac as well. Usually though, he is grouped amongst the Quackbusters ( sic) with Barrett et al.

I wouldn’t be surprised at all if one of MIkey’s folk popped up here. He supposedly has over 200k loyal followers.

Not least his terrible alcoholism NSFW

The neurosyphilis angle remains quite speculative. It seems as though there ought be to more dots to connect this one.

Blocked in the U.S.

It’s Nietzsche and a quote with which I heartily disagree most emphatically

That which fails to kill me usually leaves me with a nasty hangover.

Blocked in the U.S.

There’s nothing Nietzsche couldn’t teach ya ’bout the raisin’ of the wrist.

The neurosyphilis angle remains quite speculative.

Another theory involves Paget’s Disease.

@ Narad:

Amongst the theories about Nietzsche I’ve heard are syphylis, bipolar, schizophrenia, alcoholism, dementia.. anyone’s guess I suppose.

Although I haven’t scanned it recently, Jung wrote a great deal about Nietzsche’s psychological/ artistic views in his book on Psychological Types.

In any case, it (Nietzsche) was a favourite quote of my psychopath.

Alain

Not least his terrible alcoholism NSFW

Blocked in the U.S.

and canucksland.

Alain

Weird, since it’s just the Monty Python ‘Philosophers Song’.

Jane,

As I said, the breast cancers that arise in the BRCA mutation carriers may be biologically distinct, and many of them are morphologically distinct, which is a reflection of the underlying genetics. I suspect that the factors that influence the incidence and age of onset of those cancers are predominantly genetic, but I am not aware of any studies that attempt to disentangle the genetic factors from the environmental factors. If you are aware of any such studies, please post the references as I would be particularly interested in reading them. In any event, until such data is available, I think that we use those patients as a control group at our own risk.

I am not trying to entirely discredit this study, but I am concerned about the extent to which the data may be contaminated with things that would not be expected to progress, if at all, for a very long time. Would taking those cases out of the study change the results? I have no idea, but I think there’s a chance that it might, and for that reason, I think we need to be very careful about changing the screening protocols in reaction to this study until we have better data.

Dr. Finfer – How else do you suggest they might have gotten an estimate of what increase in breast cancer would have been seen over the past 30 years without mammography? They looked at the increase in an age group that is not routinely screened unless they are at high (or just elevated) risk; therefore there is little overdiagnosis in that group. For their extreme case, they then calculated alternate numbers based on the assumption that “real” breast cancer in over-40 women increase in frequency twice as fast. I would see no basis for making more extreme assumptions.

When you speak of the data being “contaminated” with “things that would not be expected to progress”, you’re talking about some number of real women who were told that they had (or at best, soon would have) cancer and needed to submit to treatment. Perhaps the rate of overdiagnosis could be lowered in future by taking a more conservative approach to certain conditions. However, this study was designed to estimate roughly what the actual number and percentage of overdiagnoses has been during the screening era, under the conditions that have actually been in force. Artificially lowering the overdiagnosis rate by removing people whom you agree were overdiagnosed from the data set would not give women a true estimate of what benefits and harms are to be expected from screening.

ICD-9 codes are a very blunt instrument. The way pathology coding works, we are allowed to code for what the patient is likely to have even if it is not present in the case, so there may well be patients with benign disease in this data set. Also, there is one code each for invasive breast cancer and DCIS, so the various subtypes are hidden in this study. That doesn’t even begin to address coding accuracy, which is not 100%. Therefore, I am skeptical that we really know what this study was looking at. It needs to be repeated with better data. Also, for example, as I hinted before, there are some things being called DCIS that may not be. We need to work through these issues rather that treat the entire population with a broad brush before we change our screening protocols. All I am saying is we need to be sure of what we are doing before we make changes.

Undoubtedly there are patients who are over treated, but we will never know who they are or which mammographic abnormalities are or are not likely to progress by looking at ICD-9 codes. That is a major drawback to this study,

Fair enough, but we will never get a total number of American overdiagnoses from the sort of small study that can re-examine everyone’s pathology slides. So this study does have a valid purpose. BTW, I am appalled to hear that a pathologist can code a patient as having breast cancer if he thinks she is “likely to have” it even if he sees no evidence of it! That’s a heck of a thing. But surely it is not something that has happened at skyrocketing rates in the last twenty years? And surely it doesn’t happen so often that it could be the sole explanation for a ca. 30% overdiagnosis rate?

And as for that thing that’s called DCIS that may not be: the question is, if I get a mammogram today and I have that thing, is the radiologist still going to call it DCIS, and then is the oncologist still going to tell me that DCIS is cancer and I need full-bore treatment? The authors of the study corrected for the fact that in past years there were an excess number of real cancers due to a factor, widespread pressure for long-term HRT use, which is much less prevalent today. If there were a form of overdiagnosis that was historically common but now much less prevalent, that certainly should merit a countervailing correction. If it’s still ongoing, that’s one of the risks that we have to take into account in weighing the risks and benefits of different screening regimens.

First off, a radiologist will never tell you that you have DCIS, only a pathologist can do that (via your doctor).

The treatment for DCIS is lumpectomy + radiation or mastectomy +/- hormonal therapy. As I suggested, there are indications that that may be overkill for certain forms of DCIS, and if that holds up to scrutiny, it may be necessary to call them something else. That’s still a work in progress. In the interim, those patients will continue to be treated as DCIS because that’s the standard of care.

The coding is a reimbursement issue only. If there’s nothing significant in the biopsy, and there’s nothing to code for, and your doctor indicates that he/she feels strongly that you have breast cancer, we can use that code. It has no other effect on you, but it may effect studies like this one.

Studies like this based upon coding have the advantage of being able to enroll very large numbers of patients but the disadvantages that I have described because of the way things are coded. These big studies probably represent a good start at attacking a problem (and I have no doubt that there is a problem, just perhaps not as big of a problem as this paper suggests). They need to be followed up with smaller studies containing more detailed information on each patient so we can evaluate exactly what the problem is, which entities are causing the problem, and so we can figure out what to do about it.

I am skeptical of the 30% over diagnosis rate. I suspect that it’s smaller, perhaps significantly smaller, than that, but I don’t think it’ll be possible to be sure of that one way or another without more studies,

Unless you want to presume instead that mammography directly causes a significant fraction of all cancers, there has to be overdiagnosis, because over the long term far more “cancers” will be found in a screened group than an unscreened group. And your suggestion that non-progressing DCIS should someday be given a different name (what about non-progressing Stage 1 invasive cancer, which also exists though less commonly?) does not address the current problem. I want to know, if I were to receive a diagnosis today through screening, what are the relative likelihoods of getting a lifesaving early diagnosis, a futile early diagnosis, a beneficial early diagnosis that “allows” me to avoid worse treatments, or an overdiagnosis that inflicts severe and lasting harms on me and my family for no reason. This is necessary for informed consent. The Europeans recommend screening every other year for over-50 women because annual screening has only modest additional benefit and greatly increases the opportunities for false positives and overdiagnosis. If overdiagnosis isn’t acknowledged to be a real harm, women do not have the opportunity to make decisions maximally consistent with their own values.

The answer to your question is that, except for situations in which the answer is obvious (for example, cancers that are much larger than they appear to be on the mammogram and do not cause a palpable mass), we do not know. That’s the entire point of what I’ve been saying, and that’s part of the reason why screening protocols differ in different parts of the world. We need more data.

Another part of the reason is cultural. Many Americans feel that any failure of screening is unacceptable, which makes it very difficult to make changes to screening protocols and creates an environment in which over treatment is both more likely and accepted.

A good example of that is the current furor over PSA screening for prostate cancer. We have a huge problem with over treatment of prostate cancer, and there is a great deal of resistance to the new recommendation that men of ordinary risk not be screened (this may be a major statement coming from a pathologist who had a radical prostatectomy at age 49).

There is similar push back coming from the breast cancer advocacy groups about this paper that may or may not be appropriate. Only time will tell.