One of the more depressing things about getting much more interested in the debate over how we should screen for common cancers, particularly breast and prostate cancer, is my increasing realization of just how little physicians themselves understand about the complexities involved in weighing the value of such tests. It’s become increasingly apparent to me that most physicians believe that early detection is always good and that it always saves lives, having little or no conception of lead time or length bias. A couple of weeks ago, I saw another example of just this phenomenon in the form of an article written by Dr. George Lombardi entitled My Patient, Killed By The New York Times. The depth of Dr. Lombardi’s misunderstanding of screening tests permeates the entire article, which begins with his recounting a story about a patient of his, whose death he blames on The New York Times. After describing the funeral of this 73-year-old man who died of prostate cancer, Dr. Lombardi then makes an accusation:

This one filled me with a special discomfort as I knew a secret: He didn’t have to die. I knew it and he had known it. Had he told?

About 5 years ago he had just retired and had a lot more time on his hands. He was a careful man, lived alone, considered himself well informed. He got into the habit of clipping articles on medical issues and either mailing them to me or bringing them in. They came from a variety of sources and were on a variety of topics. He wasn’t trying to show me up. He was genuinely curious. I kidded him that maybe he’d like to go to medical school in his retirement. ‘No’ he laughed, ‘I just like to be in the know.’

When he came in for his physical in 2008 he told me he’d agree to the DRE but not the PSA (his medical sophistication extended to the use of acronyms: DRE stands for digital rectal exam where I feel the prostate with my gloved finger for any abnormality and PSA for prostatic [sic] specific antigen which is a blood protein unique to the prostate and often elevated in prostate cancer). He had read that the use of PSA as a screening test was controversial. This was the year that the United States Preventive Services Task Force, a government panel that issues screening guidelines, recommended against routine PSA screens for older men. It was often a false positive (the PSA was elevated but there was no cancer), led to unnecessary biopsies, and besides most prostate cancers at his age were indolent and didn’t need to be treated. I countered that prostate cancer was the second leading cause of cancer deaths in men and that it was better to know than not to know. This way it would be our decision. The patient with his doctor deciding what was best. But no, he wanted to stick to his guns and since the DRE was normal no PSA blood test was sent.

After describing a conversation with the man’s daughter, who said, “My father was killed by The New York Times,” Dr. Lombardi then goes on to anecdotal evidence and a cherry-picked publication to support his view, quoting an oncologist who says he’s “seeing more men presenting with advanced prostate cancer” and then referring to a single paper in the current Annals of Internal Medicine about PSA screening. Before I look at the article and a recently published paper on screening mammography that made the news, I can’t help but point out that I (mostly) agree with Dr. Lombardi when he says:

Public health doctors, policy experts and journalists tend to look at the population as a whole. It is a better story if it is one story. It makes a better headline. Their statistics are people I sit across from everyday trying to figure out what the future holds. We each have our job to do.

The problem is, of course, that Dr. Lombardi takes that observation and draws the wrong conclusion, namely that his patient died because of lack of screening. He attacks a straw man, sidestepping the true argument, namely that evidence shows that PSA screening probably causes more harm than good for men at average risk of prostate cancer. Unfortunately, Dr. Lombardi obviously does not understand some very basic concepts behind cancer screening, nor does he apparently recognize that doctors who deal with the population-level data that we have regarding screening tests and try to apply them to individual patients are actually looking in a very systematic way about what the benefits of screening are to the individual patient. More on that later. In the meantime, although I wouldn’t go quite as far as Dr. John Schumann did in criticizing Dr. Lombardi, I do view his lament as a jumping off point to look at some recent data on screening for the two most common cancers, breast and prostate.

The problem with screening (yet again for the umpteenth time)

Before I get to my updates on cancer screening, to set the stage I think it’s critical to revisit these two key concepts that you must understand to understand a bit about the difficulties involved in using a screening test to decrease cancer mortality. I’ve explained them both in depth before, so I don’t feel the need to resurrect a detailed explanation again other than to boil them down to two points, with relevant links and illustrative graphs that illustrate the concept. Those who want the more characteristically (for me) verbose versions can follow the links.

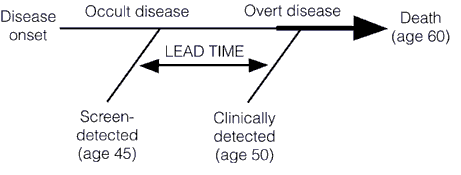

First, let’s briefly recap lead time bias, which tells us that earlier detection does not necessarily result in improvements in survival and more successful treatment. In fact, even if earlier treatment has no effect whatsoever on the natural history of a cancer, earlier detection will still give the appearance of an increase in median survival. That increase is simply the “lead time” that comes from detecting the tumor earlier (hence the term “lead time bias”), before it becomes clinically apparent on its own. This concept is illustrated below in these two graphs, first a simpler one:

And a slightly more complex one:

I have explained the concept of lead time bias in more depth here and here, but I do like that graph for illustrating the concept, as well as this one, which demonstrates the effect of lead time bias on a survival curve:

Perhaps my favorite simple and clever explanation of how lead time bias can result in apparently increased survival rates even if treatment has no effect whatsoever on a cancer’s progression comes from Aaron Carroll. It’s well worth reading.

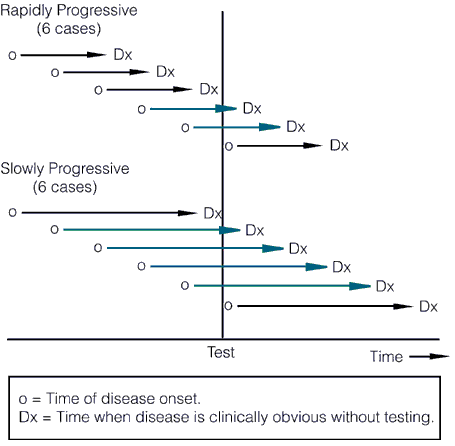

Now let’s briefly move on to length bias. It turns out that most cancer screening tests have an inherent bias towards detecting more indolent, less deadly cancers because of length time bias. Aggressive, fast-growing tumors tend to go from undetectable to clinically apparent due to symptoms, often already having progressed to an advanced stage, in a shorter time than the time interval between screening tests. These tumors thus do not count as having been detected by the screening test because they go from undetectable to symptomatic between, for example, mammography scans. The slower-growing a tumor is, the longer the length of time between its reaching the minimal detectable size of the screening test and becoming symptomatic, the longer the time there is for a screening test to detect it, as illustrated by these two graphs, beginning with this one:

The length of the arrows above represents the length of the detectable preclinical phase, from the time of detectability by the test to clinical detectability. Of six cases of rapidly progressive disease, testing at any single point in time in this hypothetical example would only detect 2/6 tumors, whereas in the case of the slowly progressive tumors 4/6 would be detected. Worse, the effect of length bias increases as the detection threshold of the test is lowered and disease spectrum is broadened to include the cases that are progressing the most slowly, as shown below:

The other problem with length bias is that the more sensitive the test, the more likely it is to detect indolent tumors that are so slow-growing that within the lifetime of the patient they wouldn’t progress to the point where they would endanger the patient’s life. Some, particularly screen-detected cancers, even spontaneously regress. Such indolent or self-limited cancers do not require treatment, but are frequently diagnosed by screening, a phenomenon known as overdiagnosis. The problem, of course, is that our ability to detect such cancers far surpasses our knowledge of how to predict which ones will regress or remain indolent. So we err on the side of aggressive treatment because we quite reasonably view the consequences of guessing wrong as being so much worse for individual patients than overtreating other patients who don’t require treatment. However, for the average patient, the odds of being helped by a screening test are rather small. For instance, to avert one death from breast cancer with mammographic screening for women between the ages of 50-70, 838 women need to be screened over 6 years for a total of 5,866 screening visits, to detect 18 invasive cancers and 6 instances of DCIS. The additional price of this was estimated to be 90 biopsies and 535 recalls for additional imaging, as well as many cancers treated as if they were life threatening when they are not. For prostate, to prevent one death from cancer, 1,410 men need to be screened over 9 years, for a total of 2,397 screening visits and 48 cancers detected. In other words, screening takes a lot of effort for, on an absolute basis, not as many lives saved as we had hoped. Moreover, in the case of breast cancer, on an absolute scale, the reduction in the risk of dying from cancer is small, as I’ve discussed, and the risks of overtreatment are high.

PSA Screening: Smarter, not harder?

Given that Dr. Lombardi cited it, I thought I’d look at the recent Annals article first. The article comes from a group at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center at the University of Washington and is entitled Comparative Effectiveness of Alternative Prostate-Specific Antigen-Based Prostate Cancer Screening Strategies: Model Estimates of Potential Benefits and Harms.

I can’t help but notice, first off, that this is a modeling paper. In other words, the investigators did what the hated U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) did in changing its recommendations for mammographic screening for breast cancer and PSA screening for prostate cancer. They took existing data and ran a bunch of computer simulations in order to model the effects of different screening regimens, noting that they were looking for ways to “screen smarter.” Of course, Dr. Lombardi’s argument is basically a straw man in that no one is saying that PSA screening is necessarily completely useless. What is being said is that there is a significant risk of overdiagnosis, overtreatment, and harm that must be balanced against the relatively small benefit of most of the recommended screening regimens. Back when radical prostatectomy was the preferred treatment for early stage prostate cancer, the risk of harm from overtreatment was significant, up to and including death, but more frequently including complications from surgery, such as incontinence, erectile dysfunction, and other less specific risks of major pelvic surgery, such as injury to the colon, bladder, and other bowel. Later, as radiation therapy supplanted surgery as the preferred treatment for very early stage prostate cancer, the potential complications, such as radiation proctitis. Dr. Schumann described these complications dramatically in his rebuttal to Dr. Lombardi’s article.

In other words, a “one size fits all” approach will not do; we need a more “personalized” approach, if you’ll excuse the term in the wake of its corruption by people like Stanislaw Burzynski. That’s exactly what the investigators on this paper (Gulati et al) tried to do.

What Gulati et al did was to model an large number of screening strategies, thirty-five in all, and then estimate the benefits and harms of each compared to the reference screening strategy of annual screening for patients aged 50 to 74 years with a PSA threshold of 4.0 g/L for biopsy referral. They also tried to validate the models when possible by seeing if it predicts incidence beyond the years of calibration (1975-2000) and to perform sensitivity analyses. Gulati et al summarize their results thusly:

Our results yield several important conclusions. First, we find that aggressive screening strategies, particularly those that lower the PSA threshold for biopsy, do reduce prostate cancer mortality relative to the reference strategy. However, the harms of unnecessary biopsies, diagnoses, and treatments may be unacceptable. Quantifying the magnitude of these harms relative to potential gains in lives saved is critical for determining whether the projected harms are acceptable.

Second, we find substantial improvements in the harm/benefit tradeoff of PSA screening with less frequent testing and more conservative criteria for biopsy referral in older men. These approaches preserve the survival effect and markedly reduce screening harms compared with the reference strategy. In particular, using age-specific PSA thresholds for biopsy referral (strategy 20) reduces false-positive results by a relative 25% and overdiagnoses by 30% while preserving 87% of lives saved under the reference strategy. Alternatively, using longer screening intervals for men with low PSA levels (strategy 22) reduces false-positive results by a relative 50% and overdiagnoses by 27% while preserving 83% of lives saved under the reference strategy. These adaptive, personalized strategies represent prototypes for a smarter approach to screening.

It should also be noted that the decrease in risk of dying of prostate cancer, even under the most optimistic scenarios in the models, was on the orders of a fraction of a percent in absolute terms. Under the models studied by Gulati et al, the risk of death due to prostate cancer without screening was 2.86% but could be reduced to between 2.02% and 2.43%, depending on the model. That’s at most a 0.84% absolute risk reduction, although on a relative scale, a decrease in risk of dying from 2.86% to 2.20% is 29%. The overall conclusion from the modeling study was that it is possible to “screen smarter” if the PSA threshold to refer for biopsy is higher, screening for men with low PSA values is decreased in frequency, and older men, who tend to have elevated PSA anyway, are screened less aggressively. All of these are not unreasonable ideas, and they illustrate the tradeoffs involved in any sort of screening program. They are also far removed from Dr. Lombardi’s straw man characterization of arguments that PSA screening can result in more harm than good as “ignorance is bliss when it comes to PSA screening.”

But what about mammography?

We also screen for breast cancer in women. The preferred test, of course, is mammography, and there is no doubt that regular mammography in women between the ages of 50 and 74 definitely reduces mortality from breast cancer. Of that much, we can be certain, although the risks of overtreatment are not insignificant. Over the last decade or so, the recommendations that screening should begin at age 40, that it should be done annually, and that it should continue for the rest of a woman’s life became the basis of public health policy with respect to breast cancer, as well as breast cancer awareness campaigns by advocacy groups. Then, in 2009, the USPSTF dropped its bombshell, in which it suggested that this screening campaign was too aggressive, resulted in too much overdiagnosis and overtreatment, and should be scaled back. Its recommendation was to begin screening for asymptomatic women at average risk (and this must be emphasized: we’re not referring to women at high risk or women who notice a lump in their breast or other symptoms) at age 50 and to perform it every two years instead of every year. I discussed this when the recommendations caused a stir three years ago, and I stand by what I wrote then.

Interestingly, a recent study from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium published in JAMA Internal Medicine a week ago (Outcomes of Screening Mammography by Frequency, Breast Density, and Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy) seems to support the findings of the USPSTF in 2009. It’s a prospective cohort study examining outcomes of women screened at mammography facilities in community practice that participate in the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) mammography registries, and the question to be answered was whether there was a difference in outcomes between women screened on a yearly basis with mammography and women who underwent screening on a biennial basis. Data were collected prospectively on 11,474 women with breast cancer and 922,624 without breast cancer who underwent mammography at BCSC facilities, so this is a large study. The study’s findings are summarized thusly:

Mammography biennially vs annually for women aged 50 to 74 years does not increase risk of tumors with advanced stage or large size regardless of women’s breast density or HT use. Among women aged 40 to 49 years with extremely dense breasts, biennial mammography vs annual is associated with increased risk of advanced-stage cancer (odds ratio [OR], 1.89; 95% CI, 1.06-3.39) and large tumors (OR, 2.39; 95% CI, 1.37-4.18). Cumulative probability of a false-positive mammography result was high among women undergoing annual mammography with extremely dense breasts who were either aged 40 to 49 years (65.5%) or used estrogen plus progestogen (65.8%) and was lower among women aged 50 to 74 years who underwent biennial or triennial mammography with scattered fibroglandular densities (30.7% and 21.9%, respectively) or fatty breasts (17.4% and 12.1%, respectively).

Leading the authors to conclude:

Women aged 50 to 74 years, even those with high breast density or HT use, who undergo biennial screening mammography have similar risk of advanced-stage disease and lower cumulative risk of false-positive results than those who undergo annual mammography. When deciding whether to undergo mammography, women aged 40 to 49 years who have extremely dense breasts should be informed that annual mammography may minimize their risk of advanced-stage disease but the cumulative risk of false-positive results is high.

In other words, in terms of reducing their risk of being diagnosed with an advanced stage tumor or a large sized tumor, it appears not to matter whether women between 50 and 74 undergo mammography every year or every other year. This is not the case when it comes to women between 40 and 49, where less frequent screening is associated with a statistically significant increased risk of being diagnosed with advanced disease. However, one has to balance that with the increased risk of false positive mammography and the absolute risk of dying of breast cancer in this age range, which is only in the range of 0.3%. This is a number that increases with age, but it is still small. For instance, Esserman et al characterized it thusly for a 60 year old woman:

Essentially, mammography reduces the odds of a 60-year-old woman dying of breast cancer in the next decade by 30%. Sounds impressive, until you look at her absolute risk: by getting her annual mammogram, her chances of dying from breast cancer are whittled from 0.9% to 0.6%. Overall, for every 1,000 women in their 60s screened for breast cancer in the next 10 years, mammograms will save the lives of 3 people but 6 others will still die. (The numbers edge up or down in lockstep with a woman’s age.)

As is often the case, this study illustrates the difficulty in balancing the risks and benefits of screening for breast cancer. Remember, the idea behind screening for a cancer — any cancer — is that detecting it early will allow early treatment, better prognosis, and a decrease in the number of people who are diagnosed with later stage cancer, which is more likely to be fatal. As a study that I discussed a few months ago showed, mammography has not reduced the number of breast cancer cases diagnosed at an advanced stage as much as one would expect, meaning that there is significant overdiagnosis. Welch’s study estimated overdiagnosis to range from 22% to 31%. From my reading of the literature, this is only a little bit higher than the rate of overdiagnosis of screen-detected breast cancers that has been estimated, namely around 20%.

The bottom line

Does this mean that we should throw up our hands and stop screening for breast and prostate cancer? Of course not! However, we have to balance the risks versus the benefits in a way that doctors like Dr. Lombardi are seemingly unable to do. Dr. Lombardi clearly views screening as an unalloyed good and believes that his unfortunate patient could have been saved if only he hadn’t listened to the NYT, which described the controversy over PSA screening for prostate cancer, and decided that it wasn’t for him. Never mind those pointy-headed docs in the USPSTF who say that PSA screening for men over 75 can’t be recommended and that balance between the benefits and the drawbacks of prostate cancer screening in men younger than age 75 years cannot be assessed, because the available evidence is insufficient. The American Cancer Society emphasizes that the decision to be screened should involve the man being screened. In any case, the danger of relying on anecdotal information, as Dr. Lombardi apparently does, is that there is no good evidence that PSA screening would have saved his patient’s life. Earlier detection could just as easily have ended up with an apparent increase in survival time that was entirely due to lead time bias. Similarly, those of us who take care of breast cancer patients have to be careful not to be seduced by the idea that mammography is some sort of panacea that will give us power over this dread disease.

The idea that finding cancer earlier almost always saves lives is a seductive one. It gives us, the physicians, the idea that we have power over cancer in contrast to how we frequently feel as though we lack such power. While there is no doubt that screening can decrease mortality from cancer, the devil is in the details. Effect sizes and absolute risk reductions are usually very small, even though they might be fairly impressive as relative values. Screening programs are resource intensive. Most importantly, nothing is free. The benefits of screening do not come without a significant cost in terms of money, overdiagnosis and overtreatment, and psychic anguish. It is entirely appropriate to openly discuss these issues, as it is not possible to have true informed consent on the part of the patient if he or she doesn’t understand the potential risks of screening, so that these risks can be balanced against the not-inconsequential benefits that screening could bring.

I’d like to conclude by putting on my scientist cap. I was once a bit like Dr. Lombardi in that I didn’t think much about screening for cancer and assumed that finding disease early is almost always a good thing. I’ve since come to appreciate that, like many things in medicine, it’s not that simple. Medicine is hard and complicated. Real hard and complicated. It’s very rare that any test or treatment is an unalloyed good or ill. Every test or treatment demands a balance between benefits and risks. Screening is no different. If admitting that to our patients and honestly discussing it with them causes us problems as a physician, then it will just have to cause us problems.

To me, the best solution will come from basic research. The shortcomings of screening, including overdiagnosis, overtreatment, lead time bias, and length bias, are not reasons to give up on screening. They are reasons to learn how to screen smarter. They are also reasons that we desperately need to understand the pathophysiology of the diseases for which we screen. After all, after finding a cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ by mammography, it would be so much better to be able to analyze, for example, its gene expression profile, and to predict whether it’s a cancer that will remain indolent or whether it’s one that’s going to progress rapidly. Prediction based on biology, be it biology as determined by genomic profiling, proteomic profiling, metabolomic profiling, or whatever combination of tests it takes, will allow us to usher in the era of true personalized medicine, in which patients receive treatment as aggressive as their disease’s biology requires or no treatment at all, if their disease’s biology tells us that it’s highly unlikely to end their lives or cause serious disability. I only hope I live to see that day.

In the meantime, we muddle through, balancing benefits and risks as best we can and, hopefully, explaining adequately to patients why we do what we do.

26 replies on “No, the New York Times did not “kill your patient.””

Thanks for a timely post on a complicated topic. As I was reading it, I began to anticipate that final sentence, and Orac delivered. On the basis of family history, my own risk is elevated, and it’s good to have this information to continue to develop a sense of proportion around risks and choices.

cookie please

I agree with THS.

I lost my sister to breast cancer when she was 36 (it feels strange still to have outlived her) – and the info in this post does make me feel more secure in my surveillance choices for myself, my daughter and my niece.

OK, the plural of anecdote is not data, but…

At age 80 (1987), my Dad had a prostatectomy for severe BPH, 4X normal size (120 g,) but not cancerous, according to my Mom.

Starting in 1999 (age 50,) I began the PSA screening as then recommended. I scored consistently below 3.5. Digital rectal exams were unremarkable, per my primary care doc.

In 2011, the DRE remained unremarkable but the PSA score had increased to 5. “Watchful Waiting” was the word.

In 2012, the DRE by my primary care doc was still unremarkable, but PSA had jumped to 7.7. I got an appointment with a urologist. The urologist found a hard nodule and scheduled me for a biopsy.

10/12 positive, Gleason score 7 (4+3) Upon “robotic” prostatectomy, the gland was 60 g, completely involved at Gleason 7 (3+4.) Fortunately the capsule was clean, as were lymph nodes. My current PSA score is below limits of detectablilty

If the current screening standards had applied one year earlier, I’d be dying, right now, from bone metastases.

My primary care doc’s DRE-skills weren’t up to the task, and he’s a good doc.

fusilier

James 2:24

Whoopsie, meant to say “two years earlier.”

fusilier

James 2:24

I do find screening fascinating. I used to be involved in prenatal screening for Down Syndrome (and neural tube defects), which required a similar juggling of risks and benefits.

Too many positive screens led to too many diagnostic amniocenteses (by cytogenetic testing), which carry a small risk of miscarriage, not to mention the anxiety a positive screen causes.

Not enough positive screens meant we missed too many cases of Down Syndrome. We screened about 5,000 pregnancies each year, and expected around 5 of those to be Down Syndrome pregnancies.

Our cut-offs were designed to generate 5% (about 250 per year) positive screen results, of which only 2 or 3 were actually Down Syndrome pregnancies, so over 200 women with normal pregnancies were subjected to the anxiety I mentioned. Even so, we would miss 1 or 2 cases of Down Syndrome each year, with a detection rate of around 75%. Another complication was that a large proportion of the women in our catchment area had religious objections to terminating a pregnancy, making it a bit pointless diagnosing Down Syndrome prenatally.

This screening was done between 15 and 20 weeks gestation. It seems like a good idea to find ways of screening earlier, as no one wants to terminate a 20 week pregnancy if it can be avoided, but it turns out that a significant number of abnormal pregnancies miscarry naturally, so you end up detecting these as well as those that would have carried to term. This is analogous to the problem of detecting breast tumors that would never progress to cancer.

Screening is always more complex than you might think.

What I came to realize is that most people have screening tests hoping for the reassurance of a negative result, something which is of value in itself, but that I think we tend to forget.

For those who choose PSA screening, the best advice I can give is not to do anything drastic on the basis of one abnormal test. Repeat it. Also, add a free PSA the second time around. That might give you some guidance as to whether you are dealing with prostate cancer or benign disease. As the last poster indicated, an increasing PSA over a long period of time is a worrisome finding.

I found myself pretty much in his situation at age 49 with a locally advanced Gleason grade 9. I am three years out from my radical prostatectomy (no way I was going to opt for radiation at that age), and I am OK so far. I had not been doing the high risk screening beginning at age 40 like I should have been doing because I had not been informed of the family history. My internist insisted on a PSA, and he hit a home run. That’s an anecdote, by the way!

I do appreciate these posts, even if they are a bit intimidating for a lay person to read through. My mother was diagnosed with a Type 2 DCIS in her early 70s, had 2 lumpectomies and eventually the entire breast removed. (She is fine now.) So there may be a diagnosis in my future as well, but based on the age it presented in my mother I’m not really in a rush to start screening, and my family physician concurs. She reminds me at every physical that I can have a mammogram if I want but based on my age and reproductive status (still functional) there’s a higher chance of a false positive. So I’ll continue to wait, I think.

@Krebiozen – I decided against amniocentesis for exactly those reasons. An initial risk assessment recommended that I get one, but my OB/GYN advised against it due to my history of miscarriages and I agreed. I had zero family history of Down syndrome and no intention of ending the pregnancy, so it was an easy decision. And my son turned out to be normal anyway.

I refused to take the Alpha-Fetal Protein screening blood test for my 2 younger kids. My OB said the test would be positive no matter what the blood test values were, because the algorithm for the test would show me at high risk simply due to my age (age 37 and 41 at delivery) which could only be resolved by an amnio which I did not wish to undergo. I did select the more comprehensive ultrasound due to my age at about 19 weeks which was reassuring (and gender-determining) and that was all I needed. Had I known what I’ve learned here about screening impacts, I might even have foregone the ultrasound, except that husband was quite anxious to know gender.

@Krebiozen–what were the false positive rates you encountered? were there any abortions of healthy children as a result?

“Watching and waithing” can be a good thing, but sometimes action is indicated. My mother was diagnosed with a slow-growing cancer of the liver, so her doctor took the “watching and waiting” position – but he didn’t act until it was much too late – my mother died of the cancer. She was very passive about her illness, let the doctor call the shots and didn’t talk to me or my sisters about it. I like to think that had I lived closer I could have talked her into changing doctors. Hindsight is wonderful. 🙁

Edith – I, too, chose not to get the test. What really ticked me off was the assumption that I was “too old” to have a healthy baby. He turned out fine – 22 & finishing up college with close to a 4.0 average.

BrewandFerment,

Your OB was quite right. Serum AFP is lower and serum beta HCG is higher in women with a Down Syndrome pregnancy, so we used a complex algorithm to generate an odds modifier from these which we then applied to the risk based solely on maternal age. This means a woman of 38 could be screen positive even if she had the same blood results as a younger woman of the same gestation who was screen negative, because of the different age related risks the calculation started with. There’s a nice explanation of all this here if anyone’s interested, though we only did second trimester screening using two markers, while Bart’s does some first trimester screening and uses more markers.

The blood screening test that I was responsible for has a very high false positive rate. Only around 3 of the 250 women we would report as screen positive would actually have a Down Syndrome pregnancy, which makes the false positive rate almost 99%. The cytogenetic test on fetal cells in the amniotic fluid sampled by amniocentesis was done by a different laboratory, but has a false positive of essentially zero since they look for 3 copies of chromosome 21 under a microscope. I’m sure errors can be made, but I have never heard of this leading to an unnecessary (if that’s the right word) abortion.

Bonnie,

There’s a table showing the risk of Down Syndrome at different maternal ages in the link I posted above. I don’t know how old you were, but even a woman of 49 has only a 1 in 25 risk of a term pregnancy with Down’s syndrome which, depending on how you look at it, aren’t bad odds.

Ironically, Medpage Today is just today pushing a study purporting to prove that octogenarians who “skip mammograms” will be “at an increased risk of dying from breast cancer.” The data set, said to “refute” the USPSTF’s opinion on screening the super-old, consisted ONLY of women over 75 who had been diagnosed with breast cancer. Those whose last mammogram had been two or more years before diagnosis had higher BC-specific death risks than those whose last mammogram had been 6 to 12 months before diagnosis. (Wasn’t anyone diagnosed within 6 months of a mammogram?) There were no data regarding possible inequities in treatment.

The article included not ONE word about the biasing effect of overdiagnosis in women diagnosed after screening mammograms, nor one word about population-level breast cancer mortality, which this study could not show to have been reduced by frequent mammography. Nor could it say anything about all-cause mortality, a real issue since octogenarians who submit to chemo are particularly likely to have their hearts destroyed. Yet Medpage Today’s Action Point summary included the claim that “this retrospective cohort study documents a higher mortality rate in older women with breast cancer who had not had a recent mammogram”, which appears to be a bald-faced lie. (Or are we to assume that octogenarians have no possible competing causes of death?)

Though you certainly have biases of your own, as everyone does, your understanding of this issue is gigantically above that of most practicing physicians. I am sure that is because you also do research and have to be capable of thinking mathematically. Far too many doctors aren’t, and when they are spoon-fed this type of propaganda, which harmonizes nicely with their existing ideological and economic interests, they swallow it readily. They then attempt to stuff it down patients’ throats, one way or another; my husband’s famously ignorant PCP ordered him a PSA test without his knowledge or consent last year. I do recognize that I know more about this particular topic than my last gynecologist because she’d been occupied learning lots of other stuff about anatomy and pharmacology that I do want her to know. But what are consumers supposed to do when their doctors barrage them with threats of death or, worse, denial of future health care?

Anyone else having a little trouble with Brewand’s implication that “Down’s syndrome” is synonymous with “not healthy”?

JGC,

Not really, because I understand what she means; people with Down Syndrome do have increased incidence of several health problems, and lowered life expectancy as compared with people with only 2 chromosome 21s. I must confess to having never really being entirely happy with some of the premises of the screening I was involved with. On meeting people with Down Syndrome I could never help thinking, “My job is to prevent people like you from being born”. Not a comfortable feeling.

@Kreb – my wife and I discussed screening during her first pregnancy. We got the ultrasound, but decided that if the baby had Downs that it was better to at least have the indication, so we’d be prepared.

Turns out we ended up dealing with something else entirely (two-vessel cord) which could have turned out badly – but it ended up okay.

Lawrence,

I assuaged my discomfort with the knowledge that I was in the business of providing prospective mothers with more information, and that it was their decision what they did with that information.

I know from personal experience that being unprepared for a non-typical baby (what is the acceptable terminology here? JGC?) can be quite a shock. My son was born with spina bifida, and we didn’t know beforehand, as the obstetrician had decided not to tell us (it was an unplanned teenage pregnancy among other complications). To be honest I’m not sure if being forewarned would have made it easier or not.

I’d like to add my anecdote, as I have done here before.

At 56, my internist’s NP did a PSA just because. Having just had a DRE that was normal, no family history, and absolutely no symptoms, I wasn’t worried. I wasn’t even worried when it came back at 7, intermediate by the standards of the lab. I saw a urologist who also found nothing on DRE, but fractionation showed protein-bound PSA at 86%, almost certainly cancer. I had a biopsy done, 4 quadrants, 3 cores each. I had 7 positive cores, from all 4 quadrants, with a Gleason score of 6. I opted for radical prostatectomy. The younger a man is at diagnosis, the more aggressive the tumor is likely to be, so action was called for. I also felt I was too young for radiation and I wanted to preserve radiation as a future option (A previously irradiated field doesn’t heal well after surgery.). At surgery the surgeon judged that the cancer was on the verge of rupturing the capsule and the final Gleason score was raised to 7.

Almost four years later, my PSA is below detectable limits. I have some minor urinary symptoms, comparable perhaps to my female counterparts who’ve had a few kids. I am probably going to have a penile implant. I am alive, just about as healthy as I have always been, and facing about a 22% chance of recurrence over the first fifteen (next eleven by now) years, but only a 1% chance of dying from it if it does recur.

Some recommend waiting to do a PSA only if symptoms or suspicious findings on exam are present. Had I done so, I doubt that my prostate ca. would have been found until I had disseminated disease, probably throughout the pelvis, maybe distant metastases; not quite game over, but all in all a much worse situation to deal with.

@JGC,

In the context of my comment, I certainly meant aborting a “not-Down’s syndrome” or whatever other variant of “not-genetically/developmentally perfect” assorted tests could turn up.

When pregnant with both of my younger kids, I received the offer of genetic counseling and it was stated that I needed to have the assorted tests soon if I wanted them. I asked why the urgency and the answer was so that we could have the results (forgot just what time milestone was presented to me but I assume it was before the end of the second trimester) in time to abort if that was my decision. So clearly the unspoken implication was of a eugenic nature and “not healthy”–as in the opposite of “no flaws found”–was the default assumption.

#6 “Another complication was that a large proportion of the women in our catchment area had religious objections to terminating a pregnancy, making it a bit pointless diagnosing Down Syndrome prenatally. ”

There is something to be said for having nine months of time in which to prepare for something.

khani,

Perhaps, that’s why I phrased it as “a bit” pointless. This was the UK NHS and it was framed to me in stark terms of cost effectiveness: the cost of the screening program vs the costs of caring for the Down Syndrome individuals whose birth the program would prevent. ‘Nice to know’ doesn’t cut it in the somewhat inhuman world of the QALY.

#21 I always like to know everything in advance if possible. One can start doing research, perhaps schedule classes or speak with multiple experts and have a game plan.

Thank you Orac!!!!

no, but misinformation about PSA tests is still out there and kicking. At bottom, it’s a diagnostic tool, but not one which should be relied upon unreservedly. Always act in concert with your physician before acting on any test results. Oh, and please stay away from the quack crap supplements that promise to “cure” your prostate.

[…] pretty technical, but this blog post about the challenge of balancing the benefits and risks of cancer screening tests is well worth […]

One of the problems with all this is that it seems obvious that if you detect cancer, and treat it, you save lives. If you do it often enough this view become heavily reinforced, because everyone that is screened and treated thinks their lives have been saved (some comments here attest to that). The trouble is the stats rarely bear this out. In the big studies of PSA vs no PSA there is usually no statistical difference in death rate between the groups, and if you do remove the prostate at the first signs of cancer there is no statistical evidence this really helps: http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-504763_162-57475720-10391704/prostate-cancer-surgery-wont-boost-survival-in-men-with-early-stage-disease-study-finds/